The industrial wilderness

7 tips for eating healthy on the trail

December 5, 2019

Moose, moose, moose

December 20, 2019

Tuesday September 24th- Jackman

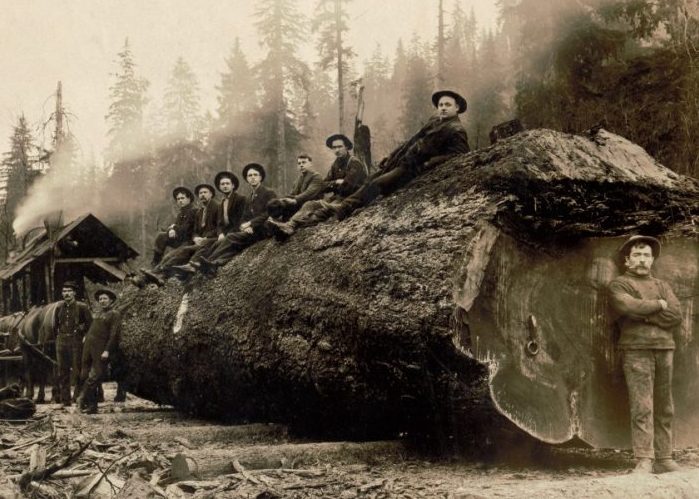

The Northern Forest Canoe Trail takes us past historic waterways, once used by indigenous people. They used canoes made of birch bark to paddle on the rivers and lakes. There were no roads and the water was by far the easiest way to get around. The first European explorers came in the 17th century, guided by the indigenous peoples. If they knew how their benevolent intentions would change history? The first European settlers came from England in the 17th century, where New England, the region in the northeast owes its name from. Fishing, agriculture, logging and whale hunting grew rapidly in those days thanks to the English. From the 19th century, demand for housing increased in major cities such as New York and Boston. The vast forests in the northeast were full of giant conifers, some with a diameter large enough for two couples to dance on it. These forest giants were cut down at a rapid pace because they were ideal for the housing industry. Much more forest was cut than there was growing. The Northern Forests were cut clear and the rivers played a leading role in this.

During the winter months, the timber companies sent thousands of loggers into the forest. They spent months in simple logging camps and worked in harsh and cold conditions. The northern forests are covered with a thick layer of snow in winter and the temperature drops far below freezing. The loggers cut down the trees and piled up all the trees next to the frozen rivers. In the spring, when the ice began to melt, the wood was pushed into the river and taken downstream to the sawmills. The huge amounts of trees were driven by "drivers" who guide the wood through the ice-cold water. They had large steel pins under the shoes to stand on the tree trunks and to pry them loose if there were congestion at rapids. The work was dangerous and several drivers died every year. The Connecticut River, where we paddled downstream a few days ago, was one of the major logging highways. About 25 million meters of wood floated over the water in the spring. The sawmills and paper mills used polluting chemicals, which strongly polluted the rivers. Ten years ago the last paper factory closed on the canoe trail and there is hardly any trace of this industrial history. We paddle through a wilderness, everything seems centuries old and untouched, but in reality the nature around us is no more than 60 years old.

Picture by Darius Kinsey/Library of Congress

Picture by forest history society

"The penultimate map already Zoë" says Olivier as he unfolds map 12.

'Gosh, how fast it is. We're going to take it slowly in the wilderness,” says Zoë convinced. Taking it easy is not our best habit, but so far we have succeeded quiet well. We want to stretch the canoe trip as long as possible.

"We're going a bit slow for Brad's pace," says Olivier. After our surprising encounter on the Spencer Stream we have been paddling together with Brad for a few days. He has a slim lightweight Kevlar canoe and goes much faster than we do. Yet our slower rhythm does not disturb him and we enjoy his company. Brad is a semi-retired surgeon from Portland, Maine. His slightly curved back shows the traces of years above the operating table. He has a calm, intelligent way of talking with a touch of dry humor. After years of working 80+ hours a week, he finally has time for himself again. He actually wanted to paddle the entire canoe trip, until his wife showed him pictures of us, dragging the canoe through the water in Vermont. He decided to start from Maine and arrived in Errol, four days after us on the trail. His wife assured him to catch up with us and say hello.

“Can I treat you guys with dinner tonight?” Brad asks.

"You treated us with this cabin already" we almost say in unison.

"That is my pleasure and my way to introduce you to become a Mainer" is his confident answer.

When we arrived this afternoon in Jackman, the last village until the end of the trail, Brad treated us and himself to a wooden cabin next to the lake. He first wanted to pay two cabins, one for us and one for himself, so that we had more privacy. We quickly transformed the cabin into a gigantic mess with unpacked bags, drying clothes and sleeping bags. It always turns out like this. Everything is organized in our bags, but once we are under a roof, it becomes a mess.

"My wife feels much more comfortable that I found some companions," Brad tells us. "Maybe we can paddle together until the Chase Rapids, because it's safer to do rapids in groups," he proposes with a slight doubt.

"Sure, but we will take our time and don't rush through the trail," Zoë says with her answer.

"That's fine, I like your company and if I don't bore you yet, I would like to paddle together," he says with his calm voice.

"Sound like a plan, and Zoë's parents will be happy too" winks Olivier. Brad has a satellite phone that forwards a location every ten minutes to an online map that everyone can follow. If we tell Zoë's parents, they will follow every paddle stroke of our canoes.

After Jackman we have to paddle twelve days through industrial wilderness. There are no villages, no shops, no facilities, only vast forests and wild nature. We pick up our food package at the post office and buy extra food in the small supermarket. We have two large waterproof bags with food, sufficient for a minimum of thirteen days. We hardly get our backpack off the ground and Brad looks at us with big eyes when he sees how much we eat. He has a small stock of freeze-dried meals and some nut mixes.

"Be prepared Brad, you're more than a week on the trail, your appetite will come" we laugh with his lean appetite.

"I want to get back in shape so I don't want to eat more" and he gives us a bag of nuts that doesn’t fit in his bag. We have always space for extra food.

After forty days in the canoe we aren’t beginners anymore and well trained. Still there are a few challenges coming up. The lakes in Maine are big, vast and poorly protected from the wind. You can get trapped for a few days due to strong winds, our guidebook tells us. Moosehead Lake is one of those big lakes, but when we leave early in the morning, there is no breath of wind. We paddle in a cool sunrise. Brad left a little later, but soon catches up with us.

"Can I give you some tips?" He asks cautiously

"Please!” Zoë says and we get a few handy tips to paddle more efficiently.

"Too bad we didn't meet you on the second day,” Olivier laughs when he has checked the efficiency of the new paddle technique with the GPS. "We go almost one kilometer an hour faster."

The wind picks up a little, but it comes from the south and pushes us forward. We cross the lake in just four hours, while it would be a whole day in our schedule.

"That's how we catch up half a day of our schedule," says Olivier as we dock on the other side of the lake.

"Well, we'll do a few kilometers less tomorrow"

We have to walk five kilometers to the next river and unfold our wheels. Soon we are surrounded by small, black flies. It immediately reminds us of the days on the Appalachian Trail where we were sometimes terrorized by the flies all afternoon.

"I have never seen black flies in this time of the year," says Brad as he looks at the cloud of black flies around his head.

"Are these the famous black flies," Zoë asks. Everyone is talking about the terrible period in the spring when the ice has just melted. Black fly season begins, being outside is hell, thousands of small flies swarm around your head, crawl into your pants and sleeves, they drive you crazy.

"There are so many that they black out the sun," Brad laughs, still surprised.

A jeep is coming our way with two hunters in it. They wear orange hats and coats so they don't get confused with a deer when they hunt.

"Oh yes, they are here all the time. Black snow we call it" one of the two men laughs when we ask if it is normal that there are black flies.

There is no other option than putting on our hood and walk on.

"You're mentally not prepared for the black flies I see," says Brad when he gives Zoë a head net. It doesn't bother him that much, clearly used to more flies than this.

The other big challenge follows a few days later. Our guidebook describes the portage as "character building" and "soul destructing". We have been looking forward to this portage since the start of the canoe trip. It reminds us of the special border crossing between Chile and Argentina on the way to the end of the world. Many cyclists described that as an emotional victory, while we walked through the mud with a big smile. We look forward to seeing the mud bath. The Mud Pond Carry is a three-kilometer stream, no wider than half a meter. The ground consists of sucking mud, sometimes deeper than the ankles. Fallen trees cause extra obstacles and in the spring the mosquitoes swarm around your ears. Fortunately we have no problems with the latter, the other ingredients are present in abundance. Brad drags the canoe behind him like in the Little Spencer Stream and soon disappears out of view. If the stream is wide enough, we drag the canoe over the mud. In other parts we balance with the canoe on our shoulders while our feet are sucked into the mud. After a while we catch up with Brad, who is taking a break. We just crawl over a fallen tree trunk with the canoe on our shoulders and carry a backpack with a food supply with eight days on our backs. Brad stares at us with a grin.

"I am very impressed guys. You're one of the strongest people I have ever met"

"Well, I hope I can do what you do when I am 66," puffs Olivier, who has at least the same amount of respect for Brad's condition.

"You will, looking at the life you're living now. I don't think you will sit in a couch after this canoe trip."

Two and a half hours later we are on the end of the Mud Pond and give Brad a high five. "That was fun," he laughs.